Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe

Archdiocese of Santa Fe Archidioecesis Sanctae Fidei in America Septentrionali Arquidiócesis de Santa Fe | |

|---|---|

Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Territory | 19 counties in Northeastern New Mexico |

| Ecclesiastical province | Santa Fe |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 61,142 sq mi (158,360 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2014) 1,473,000 323,850 (22%) |

| Parishes | 93 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | July 19, 1850 (174 years ago) |

| Cathedral | Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi |

| Patron saint | St. Francis of Assisi[1] |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Archbishop | John Charles Wester |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| archdiosf.org | |

The Archdiocese of Santa Fe (Latin: Archidioecesis Sanctae Fidei in America Septentrionali, Spanish: Arquidiócesis de Santa Fe) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the southwestern region of the United States in the state of New Mexico. While the mother church, the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, is in the city of Santa Fe, its administrative center is in the city of Albuquerque. The current archbishop is John Charles Wester, who was installed on June 4, 2015.

The archdiocese filed for bankruptcy in June 2019, followed by a bankruptcy plan in October 2022.[2][3]

Territory

[edit]The Diocese of New Mexico comprises the counties of Rio Arriba, Taos, Colfax, Union, Mora, Harding, Los Alamos, Sandoval, Santa Fe, San Miguel, Quay, Bernalillo, Valencia, Socorro, Torrance, Guadalupe, De Baca, Roosevelt, and Curry.

History

[edit]Spanish jurisdiction 1500 to 1821

[edit]The history of Catholicism in New Mexico began in the early 17th century, with the arrival of the Spanish settlers. Spanishs conquistadors had passed through the region as early as 1527 in search of gold and silver as early as 1527. However, there were no Spanish settlements until 1698, when the explorer Juan de Oñate arrived from New Spain with 500 Spanish settlers in present-day Santa Fe.[4]

De Oñate was accompanied by ten Franciscan priests who built the first Spanish missions in New Mexico.[5] By 1608, the Franciscans converted over 7,000 Puebloans to Catholicism.[6] The Franciscans in 1610 constructed the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe with labor provided by Tlaxcalans from Mexico. It is considered one of the oldest churches in the United States.

While they attended mass and followed other Catholic traditions, the Puebloans continued to practice rituals and customs from their own religion.[6] The Franciscans attempted to outlaw the use of entheogenic drugs in Puebloan religious ceremonies and seized Puebloan masks, prayer sticks, and effigies. During the 1650's, the Spanish governor of New Mexico, Bernardo López de Mendizábal, attempted to protect the Puebloans' rights by enforcing labor laws and allowing them to hold their own religious ceremonies. In response, the Franciscans denounced de Mendizábal to the Mexican Inquisition. He was removed from office and convicted in Mexico City of heresy.[7] t churches in the United States).

In 1680, the Spanish administration in Santa Fe arrested 47 Puebloan medicine men and executed four of them. Drawing on decades of anger and frustration, the Puebloan religious leader Popé led his people into the Pueblo Revolt against the Spanish.[8] The insurgents killed 400 Spanish and 21 of the 33 Franciscans in the region. He forced the Spanish, along with Puebloan converts to Catholicism, to flee Santa Fe to El Paso del Norte in present-day Chihuahua.[9] Following the revolt, the Puebloans destroyed all Catholic buildings and religious items in the area, then cleansed themselves in a ritual bath. [10]

In 1692, the Spanish regained control of Santa Fe from the Puebloans and the Franciscan priests returned with them. However, the authorities now allowed the Puebloans to practice their traditional rituals, ceremonies, and religion.[10] According to the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, the period from 692 to 1821 was a time of reconciliation and growth between the Puebloans and the Spanish. While there were still abuses and reprisals on both sides, a "truly unique" form of Catholicism emerged that reflected the culture and history of the area.[11]

Mexican jurisdiction 1821 to 1848

[edit]

With the end of the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, New Mexico became part of the new First Mexican Empire.[12] New Mexico and large stretches of the future American Southwest were part of the Diocese of Durango headquartered in Durango, Mexico.Most of the Spanish clergy withdrew from New Mexico at this time, leaving most of area without any priests.

In 1833, Pope Gregory XVI appointed Reverend José Antonio Laureano de Zubiría y Escalante, a Mexican cleric, as bishop of Durango.

American jurisdiction 1848 to present

[edit]

In 1848, Mexico ceded New Mexico along with other territories to the United States with the end of the Mexican–American War. As a Mexican bishop based in Mexico, Zubina's diocese now included territory that belonged to another nation.

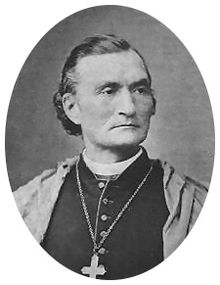

On July 19, 1850, Pope Pius IX erected the Vicariate Apostolic of Santa Fe, which included all of New Mexico and parts of Texas and Arizona. He named Reverend Jean-Baptiste Lamy, a Frenchman, as the vicar apostolic.[13]

Lamy arrived in Santa Fe in 1851. However, Reverend Juan Felipe Ortiz, administrator of the Catholic Church in New Mexico, told Lamy that he and his Mexican priests were still under the jurisdiction of Zubiría.[14] Lamy wrote to Zubiría asking him to resolved the conflict, but Zubiría never answered him. In November 1851, Lamy traveled to Durango and showed Zubiría the papal document of his appointment; Zubiría was forced to tell his priests that they now reported to Lamy.[15] However, Zubiría retained jurisdiction over the parishes in Southern New Mexico. Zubiría appointed Reverend José Jesus Baca to supervise this area.[16]

In 1853, the Vatican elevated the vicariate apostolic into the Diocese of Santa Fe, with Lamy as its first bishop.

Lamy soon ran into conflict with the Mexican clergy. According to Author Anthony Mora, Lamy introduced European and American clergy to the vicariate as a way to displace Mexican priests and "Americanize" the Catholic Church there, creating tension with the Mexican-American congregants and clergy. Many of the new priests believed that assimilation to American culture was vital, and they used racist ideas to justify the changes that they were making to the Catholic Church. [16]

One of Lamy's controversial actions was the outlawing of the Penitente Brotherhood. The Penitentes came to popularity in New Mexico in the 1820s following Mexican independence. The Catholic hierarchy in Rome was uncomfortable with the Penitentes, mainly because of their use of flagellation. He also banned concubinage and excommunicated five Mexican priests who were in sexual relationships with women, including Reverend José Manuel Gallegos. Gallegos later served in the US House of Representatives.[17] [18][19] Lamy started construction of a new cathedral with European styles instead of Mexican ones. He reinstituted tithing to the archdiocese and threatened to withhold sacraments from any congregants who refused to comply.

Reverend Antonio José Martínez from Taos, New Mexico, compiled a list of grievances against Lamy, cosigned by many Mexican priests.[20] Lamy suspended him from performing his priestly functions, but Martinez continued to celebrate masses. Lamy finally excommunicated him in 1858.

The Vatican in 1868 reduced the size of the Diocese of Santa Fe by creating the Vicariate Apostolic of Arizona and the Vicariate Apostolic of Colorado-Utah.[13] In 1875, the Vatican elevated the Diocese of Santa Fe into the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, with Lamy as its first archbishop.[13]

The Mexican Americans who held control over the southern New Mexico parishes gradually began to lose power to the Euro-Americans. This time period proved to be a time of intense conflict between the Mexican Americans and the Euro-Americans. The Mexican Americans living in this area dealt with extreme difficulties as a result of their faith.

Sex abuse claims and bankruptcy

[edit]The archdiocese announced it would file for bankruptcy protection on November 29, 2018, in the wake of dozens of ongoing lawsuits stemming from a sexual abuse scandal that stretches back decades.[21][22] A new investigation was also ordered by the state's attorney general into the Catholic Church's handling of misconduct by its clergy.[21][22] On June 21, 2019, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy after it was announced that there were 395 individuals suing the Archdiocese for past sex abuse.[2]

Prior to filing for bankruptcy, the Archdiocese transferred assets worth over $150 million into trusts and its incorporated parishes. In October 2020, a bankruptcy judge ruled that abuse survivors could file lawsuits alleging these transfers were a fraudulent attempt to avoid bigger payouts to victims.[23] It has also been alleged that such a strategy fits into a larger pattern of similar asset-shielding from abuse-related bankruptcy filings nationwide by the Catholic Church.[24]

As of April 2024, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe remains in bankruptcy, with at least one claimant alleging that one major term of the settlement, the way the archdiocese agreed to list credibly accused clergy, was still being violated by church officials.[25]

Bishops

[edit]

Vicar Apostolic of New Mexico

[edit]- Jean-Baptiste Lamy (1850–1853), title changed to Bishop of Santa Fe with erection of diocese

Bishop of Santa Fe

[edit]- Jean Baptiste Lamy (1853–1875) elevated to Archbishop

Archbishops of Santa Fe

[edit]- Jean-Baptiste Lamy (1875–1885)

- Jean-Baptiste Salpointe (1885–1894; Coadjutor Archbishop 1884–1884)

- Placide Louis Chapelle (1894–1897; Coadjutor Archbishop 1891–1894), appointed Archbishop of New Orleans and later Apostolic Delegate to Cuba and Puerto Rico and Extraordinary Envoy to the Philippines

- Peter Bourgade (1899–1908)

- John Baptist Pitaval (1909–1918)

- Albert Daeger, OFM (1919–1932)

- Rudolph Gerken (1933–1943)

- Edwin Byrne (1943–1963)

- James Peter Davis (1964–1974)

- Robert Fortune Sanchez (1974–1993)

- Michael Jarboe Sheehan (1993–2015)

- John Charles Wester (2015–present)

Auxiliary bishops

[edit]- John Baptist Pitaval (1902–1909), appointed Archbishop of this archdiocese

- Sidney Matthew Metzger (1939–1941), appointed Bishop of El Paso

Other priests of this diocese who became bishops

[edit]- Arthur Tafoya, appointed Bishop of Pueblo in 1980

- (Jeffrey Neil Steenson, former Episcopal bishop and later priest of this archdiocese, was appointed Ordinary of the Chair of St. Peter in 2012 but could not become a Catholic bishop)

Churches

[edit]

Cathedral

[edit]Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy started construction on the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi (commonly known as the St. Francis Cathedral) in 1869. It would be the third church to occupy the portion of land. The first was a chapel constructed by Franciscan Friars in 1610 which was destroyed in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680; the second was an adobe parish church built in 1717 which St. Francis Cathedral replaced. Construction was not finished until 1884, by which time, the diocese had become the archdiocese, and the cathedral – dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi – became its mother church. Archbishop Lamy is entombed in the sanctuary floor of the cathedral, and a bronze statue, dedicated in 1925, stands in his memory outside the front entrance of the cathedral.

It was built in a Romanesque style found in Bishop Lamy's native France. The interior reflects the pastel colors of New Mexico; The pews are made of blonde wood, and the walls and columns are painted a dusky pink with pale-green trimmings. Stone for the building was mined from what is now Lamy, New Mexico - named in the Archbishop's honor – and the stained glass was imported from France. The cathedral was originally intended to have two spires rising up from its landmark bell towers, but due to costs, this was delayed, and finally canceled, giving the bell towers a very distinctive look.

Conquistadora Chapel

[edit]The adjoining Conquistadora Chapel is all that remains of the second Church. Built in 1714, this tiny Chapel houses La Conquistadora, the oldest Madonna in the United States, brought by Franciscan Friars in 1626.[citation needed]

Elevation to a basilica

[edit]On June 15, 2005, Archbishop Sheehan announced that Pope Benedict XVI had designated the cathedral a basilica. The cathedral was officially elevated on October 4, 2005. Its full name, the Cathedral of Saint Francis of Assisi, was consequently changed to the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi. Elevation of Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis - Archdiocese of Santa Fe

Loretto Chapel

[edit]The archdiocese is also the home of the Loretto Chapel, which contains an ascending spiral staircase—the building of which the Sisters of Loretto consider to be a miracle due to the unusual construction of the staircase (see Loretto Chapel for a more detailed discussion).

Education

[edit]High schools

[edit]- St. Michael's High School – Santa Fe

- St. Pius X High School – Albuquerque

Suffragan sees

[edit]

See also

[edit]- Anton Docher

- Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Church in the United States

- Ecclesiastical Province of Santa Fe

- Catholic Church by country

- Jean-Baptiste Lamy

- List of Catholic archdioceses (by country and continent)

- List of Catholic dioceses (alphabetical) (including archdioceses)

- List of Catholic dioceses (structured view) (including archdioceses)

- List of Catholic cathedrals in the United States

- List of Catholic dioceses in the United States

- Loretto Chapel

References

[edit]- ^ "Pastoral Letter on the 150th Anniversary of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe".

- ^ a b "395 claims filed in church bankruptcy case".

- ^ "Santa Fe archdiocese files bankruptcy plan". Associated Press. 2022-10-12. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^ Simmons, Marc (1991). The last conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the settling of the far Southwest. The Oklahoma western biographies. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 96, 111. ISBN 978-0-8061-2338-7.

- ^ Riley, Carroll L. (1995). Rio del Norte: people of the Upper Rio Grande from earliest times to the Pueblo revolt. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. pp. 247–251. ISBN 978-0-87480-466-9.

- ^ a b Forbes, Jack D. (1960). Apache, Navaho, and Spaniard (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 112. LCCN 60013480.

- ^ Sanchez, Joseph P. "Nicolas de Aguilar and the Jurisdiction of Salinas in the Province of New Mexico, 1659-1662", Revista Complutense de Historia de América, 22, Servicio de Publicaciones, UCM, Madrid, 1996, 139-159

- ^ Sando, Joe S. (1992). Pueblo nations: eight centuries of Pueblo Indian history (1st ed.). Santa Fe, N.M: Clear Light. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-940666-07-8.

- ^ Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing. "Antonio de Otermin and the Pueblo Revolt of 1680[permanent dead link]." New Mexico Office of the State Historian, accessed 13 Dec 2016.

- ^ a b Kessell, John L. (1979). Kiva, cross, and crown: the Pecos Indians and New Mexico, 1540-1840. Washington: National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Print. Off.

- ^ "400 Years of Catholicism in New Mexico - Archdiocese of Santa Fe". www.archdiocesesantafe.org. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ^ Guedea, "The Old Colonialism Ends", pp. 298–299.

- ^ a b c "Santa Fe (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2025-02-13.

- ^ Lucero 2009, p. 242.

- ^ Lucero 2009, p. 244.

- ^ a b Mora, Anthony P. (2011). Border dilemmas: racial and national uncertainties in New Mexico, 1848–1912. Durham, [N.C.]: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4783-5.

- ^ "Definition of CONCUBINAGE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ^ Rogin, Michael (1975-10-05). "Lamy of Santa Fe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ^ Horgan, Paul (2003). Lamy of Santa Fe (1st Wesleyan University Press ed.). Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6532-7.

- ^ "New Mexico Office of the State Historian | people". newmexicohistory.org. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ^ a b "Archdiocese of Santa Fe to file for bankruptcy". Las Cruces Sun-News.

- ^ a b Haywood, Phaedra (9 November 2018). "Archdiocese of Santa Fe faces 5 new sex abuse suits". Santa Fe New Mexican.

- ^ "Judge: Victims can sue Santa Fe Archdiocese over transfer". AP News. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Saul, Josh (8 January 2020). "Catholic Church Shields $2 Billion in Assets to Limit Abuse Payouts". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Hardin-Burrola, Elizabeth (April 17, 2024). "Santa Fe Archdiocese back in court as abuse survivor claims violation of settlement". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe

- Catholic Church in New Mexico

- Religious organizations established in 1850

- Roman Catholic dioceses and prelatures established in the 19th century

- 1850 establishments in New Mexico Territory

- Roman Catholic dioceses in the United States

- Companies that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2019